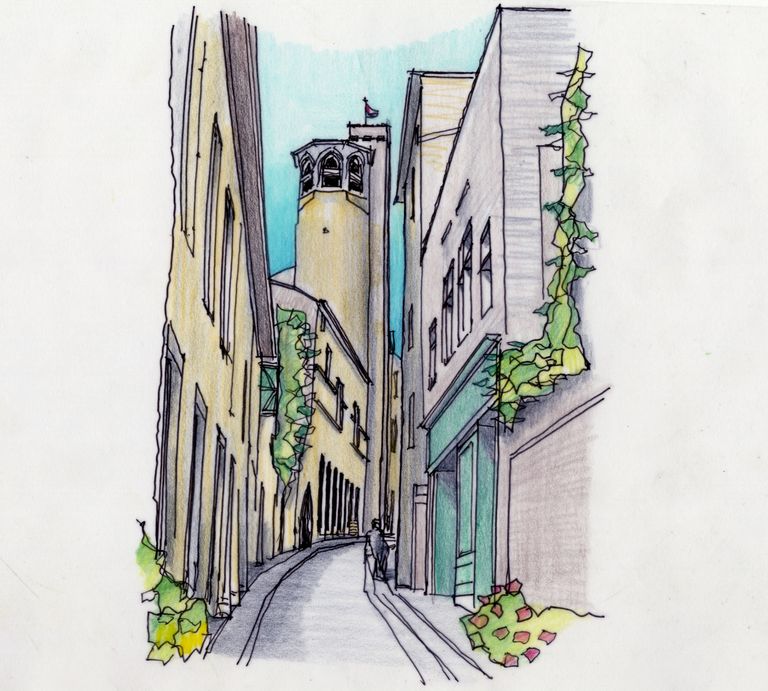

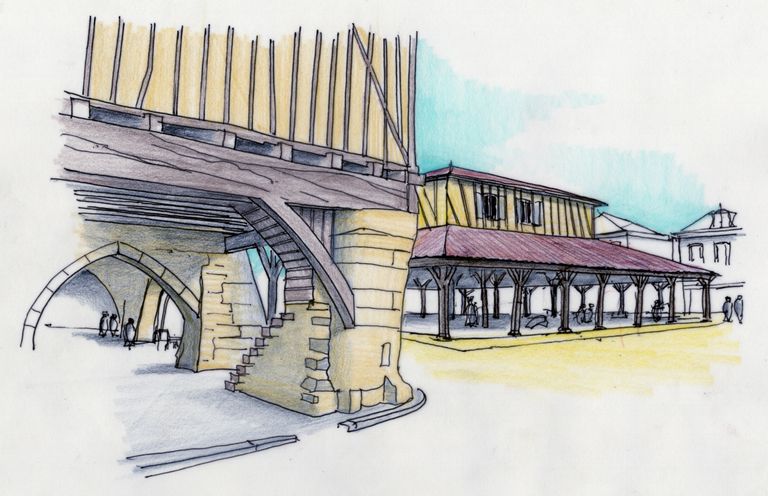

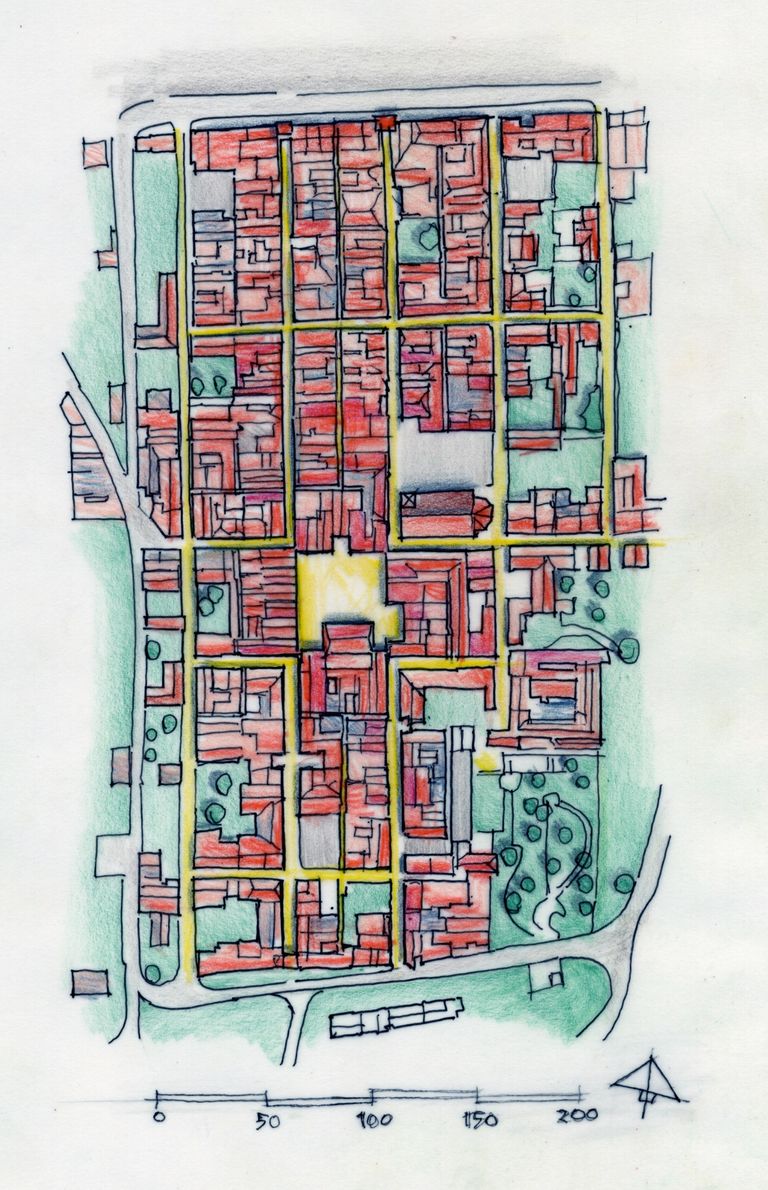

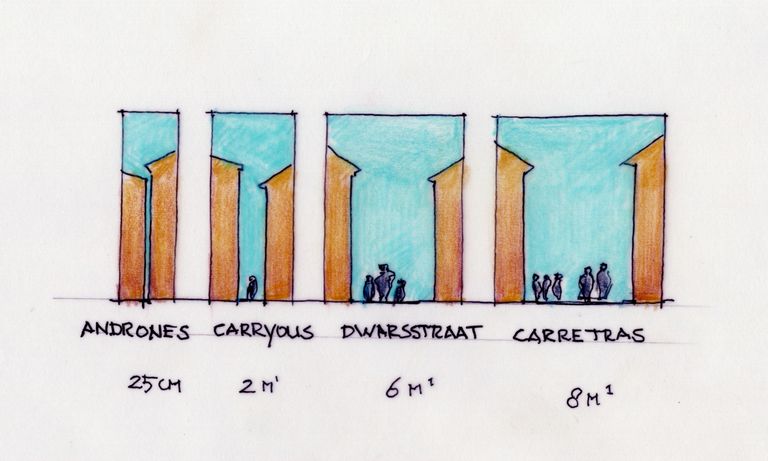

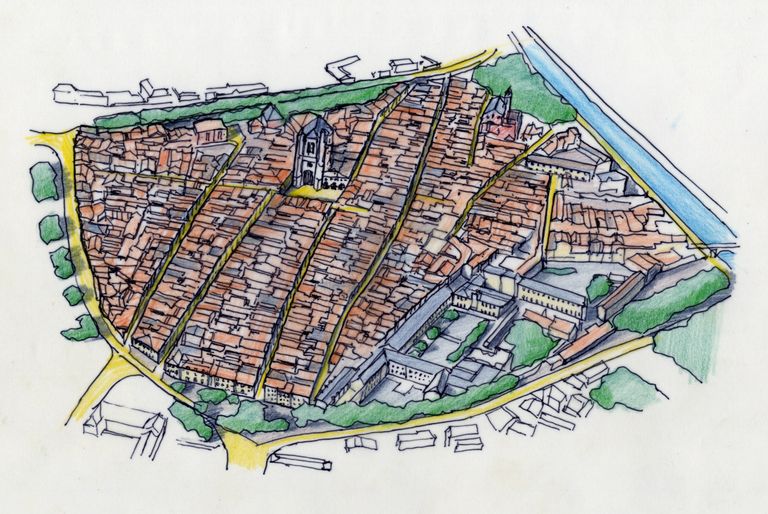

The street plan consists of five main streets running east–west, two main streets running north–south, and numerous narrow side streets, resulting in narrow, deep plots. The market square and the church are in the northern part of the city, not in the centre as in other bastides. The square is a fine example of what characterises many bastides: all its sides are lined with arcades, forming a continuous façade with several cornières. The buildings are three storeys high with steep roofs, befitting the urban character of this place. The true peculiarity of Villefranche-de-Rouergue is that the church, the Collégiale Notre-Dame, stands on the market square, with its tower directly on the square and the arcades. Indeed, the arcade even passes beneath the church! The intention was to outshine the cathedral of Rodez, but due to lack of funds the tower reached only 58m, while the cathedral’s tower stood 87m tall. Because of the church’s positioning, the market hall was later— in the 19th century—built at the edge of the town, behind the church.