In Search of the Modern in the Ancient City

When you think of Rome, you think of history, of an ancient city. This city is the cradle of our civilisation. The Roman Empire existed from 753 BC to 476 AD. At its peak, it covered an area from Scotland to Iran and from central Germany to southern Egypt, an area of some six million square kilometres with 120 million inhabitants. Remarkably, cities played a crucial role (interconnected by water and roads) for the transport of goods and people. What do you search for as you walk through Rome? What remnants of the foundations of our civilisation can still be seen? Due to the focus on the ‘old’, there is – compared to other cities – less attention on the ‘new’. We set out to discover how this city gives space to modern and contemporary art.

In Rome, there is no other way than to start with history, specifically with V. Despite the name suggesting it is just a villa, this is actually a large public park north of the city centre. From 1580, it was an estate owned by the family of Cardinal Scipione (1576–1633). It later became the prestigious residence of the noble Ceuli family. Its heyday came at the end of the 18th century, when the property came into the possession of Marcantonio IV Borghese (1730–1800). Through the purchase of adjacent lands and vineyards by his son, the estate expanded to 80 hectares. The Borghese family was known for its hospitality, and the park was opened for festivities; there was even a theatre in the park. The park is situated on the Pincian Hill. If you ascend via the famous Piazzo del Popolo, you are treated to a beautiful view of the city from the terraces. On the other side of the Tiber River, you can see St. Peter's Basilica. In our search for modern art, we are already rewarded at the Terraza del Pincio with a delightful temporary exhibition: Botero in Rome, running from July to October 2024. Fernando Botero was a Colombian painter and sculptor. He became especially well known for his ‘chubby’ bronze sculptures of human and animal figures. Nearly a year after his passing, Rome honours the artist with a museum exhibition and an open-air display at six different locations. Here, we encounter two reclining female figures.

In the 19th century, the park was transformed into an English landscape garden. The entire Borghese family estate became state property in 1901. The gardens were purchased by the city of Rome in 1903 and have been open to the public ever since. The park houses various villas and even a zoo, the Bioparco di Roma. The oldest building, dating from 1613, is the Casino Borghese, which has served as the national museum for Renaissance art, the Galleria Borghese, since 1903. One of the most remarkable buildings in the park is not one of the old villas, but the Globe Theatre. It is a full-scale replica of the wooden Shakespeare Theatre in London. It was built in just three months in 2003 by the Silvano Toti Foundation. Unfortunately, it has been closed since September 2022 after a staircase collapse injured 12 people. Still, it’s a beautiful idea to build a theatre in the park, just like the Borghese family once did.

The first museum we visit is one you might easily overlook: It is housed in a small building on the edge of the park. At first glance, it may not appear significant but looks can be deceiving. The building stands on the site where the first villa was once built. Due to civil unrest – which eventually led to the fall of the Roman Republic in 1849 – the original structure was bombed. From the ruins, this building was freely constructed as an orangery, a winter shelter for citrus trees. Owned by the city since the early 20th century, the building has served various purposes, including as lodging and office space. It is a small-scale structure with two floors. Due to its location, you can enter from Viale San Paolo del Brasile at the lower level and exit into the park at the top. In a patio, you get the sense that the reconstruction of the path happened in a romantic spirit. A fountain shaped like a small chapel was created using pebbles and shells. Two bronze sculptures in the lower garden already hint that this is a place where you’ll find modern art. Here stand the life-sized bronze sculptures ‘Cardinale’ by Giacomo Manzù (1908–1991) and ‘Hector and Andromache’ by Giorgio de Chirico. These sculptures are part of Carlo Bilotti’s permanent collection.

Carlo Bilotti (1934–2006) was the son of the noble Mario and Edvige Miceli, entrepreneurs with factories and construction sites. He studied law in Naples and Palermo. During a visit to Columbia University in New York, he met his wife, Margaret Embury Schultz. In 1973, he became president of the Jacqueline Cochran company in New York. This company produced perfumes for some of Europe’s most renowned cosmetic brands such as Nina Ricci, Carven, and Pierre Cardin. Under his leadership, the company expanded into Europe, and Bilotti became active in the world of finance and art in Zurich, Basel, and London. He became an art collector and developed friendships with artists such as Giorgio de Chirico, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Salvador Dalí, Niki de Saint-Phalle, Larry Rivers, and Rotella. In the final years of his life, he felt the need to share his private art collection with the public. During that time, he moved between Palm Beach, New York, and Rome. The Carlo Bilotti Museum opened in 2006.

The museum’s permanent collection consists of 22 works of art, including paintings, drawings, and sculptures. Of these, 18 are by Giorgio de Chirico. The museum also hosts temporary exhibitions. Carlo Bilotti and his family are featured in two portraits in the museum. The first, of Tina and Lisa Bilotti, was created in 1981 by Andy Warhol. It is a subtle semi-photographic interpretation of the subjects. Particularly noteworthy is that there are two people depicted on a single canvas, which was not common in Warhol’s work: Tina, Carlo’s wife, and their daughter Lisa, who tragically passed away in 1989. The second portrait, ‘Carlo with a Dubuffet in the Background,’ is a relief painting by Larry Rivers (1994). The work by Jean Dubuffet in the background is also part of the Bilotti collection. Jean Dubuffet is well known in the Netherlands for his large-scale work ‘Jardin d’émail’ in the sculpture garden of the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, created in 1973.

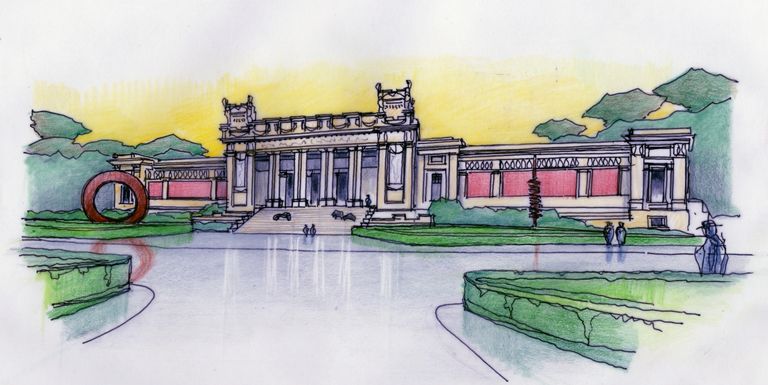

We take a step from one of the smallest to the largest museums, both located in Villa Borghese park. Walking from the Carlo Bilotti Museum, you pass a pond where you can row small boats. A little further on – at the top of the hill in the park – you get an overwhelming view of the museum of modern art: the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, commonly known as . You see an immense building with a pediment and columns at the front. On the stairs leading to the elevated terrace are three large lion sculptures by the Italian sculptor Davide Rivalta. These sculptures were installed in 2013 as part of a project exploring the relationship between art and public space.

The museum was originally founded in 1883 and was initially housed in the Palazzo delle Esposizioni. It moved to its current main building in 1915. This building, located on the Viale delle Belle Arti, dates back to 1911 and was designed by Cesare Bazzani. It was expanded in 1933–1934. I later read that a new building for the museum was designed by Luigi Cosenza and constructed in 1988, but it was closed ten years later for safety reasons. An award-winning proposal by the Swiss architecture firm Diener & Diener from 1999–2000 to replace Cosenza’s building with a new one was halted in 2003. It was later decided to preserve Cosenza’s building after all. This is the building we visited.

You might call it a professional quirk, but we always look for evacuation maps in buildings. Not necessarily because we want to scout out escape routes in advance, but because these maps give you a layout of the building. This building is so large that nowhere inside do you get a full overview of the floor plan. You only see the immediately adjacent rooms each time. Even on the museum’s own website, there’s no map available, so we’ll have to rely on a description. The grand staircase at the front brings you to the entrance hall and the Salle delle Colonne (hall with columns). On either side, you can enter a large gallery, each of which gives access to several smaller rooms. If you go straight ahead, you enter the central hall and get a glimpse of the outer courtyards named Kosuth (left) and Alvorandi (right). If you continue even further, you reach the Cortile Centrale (central courtyard), which, like the hall with columns, opens into several rooms on both the left and right. You can also walk through the smaller exhibition rooms to move from one gallery to another. That’s essentially how you navigate the museum. But honestly, you quickly lose your way. Not surprising when you realise there are 5,000 paintings and sculptures displayed in 75 rooms.

There are constant changes in elevation: the central section and ends of the museum are on higher levels, while the rooms in between are lower. The central halls have ceilings at least 10 metres high, and the smaller rooms nearly 8 metres. A remarkable feature is that you’re continuously looking through high openings from one room into another – there are hardly any dead ends. Another unique aspect of this museum is the combination of art. Artworks from different periods are displayed together. In one of the first rooms, for example, you'll find 19th and early 20th century paintings densely hung on the wall, interspersed with monitors showing video art from the 20th or 21st century. This makes walking through the many rooms incredibly engaging. After some searching, we find the museum’s café-restaurant, which has an excellent menu. We later discovered that the restaurant is easily accessible from the outside, so you don’t need to go through the museum to get there — much more convenient.

For the next part of our search for contemporary art in Rome, we didn’t have to go far. Just east of Villa Borghese is — short for Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Roma. Museo MACRO is located on Via Nizza in a former Peroni brewery. The museum is known for its innovative and bold exhibitions, showcasing modern art movements and interdisciplinary projects. Unfortunately, when we visited, it was between exhibitions, so there wasn’t much art to see. Fortunately, our interest in architecture gave us plenty to explore.

Peroni beer has been brewed in Rome since 1864, and you can still find various old buildings in the city related to it. In 1971, brewing activities at the Via Nizza building ended. A renovation plan was developed with the owner and the municipality, and between 1978 and 1982, part of the complex was donated to the city to house social activities for the neighbourhood. In 1984, the City of Rome acquired the property and turned it into the municipal gallery for modern and contemporary art. Renovation began in 1996, and the complex was opened in 1999. During the renovation, the Via Reggio Emilia façade was redesigned, load-bearing structures were reinforced, the roof was rebuilt, internal spaces were reconfigured, and the building layout was revised. After the restructure, it became clear that both the exhibition space and storage capacity for collections were largely inadequate.

In 2000, the City of Rome announced an international architecture competition to add extra space to the building and improve the overall function of the complex. A key requirement was that the new spaces had to suit the diversity of contemporary artistic production while remaining connected to both the existing building and its surroundings. In 2001, the expansion design was awarded to French architect Odile Decq, and construction began in 2004. The museum reopened to the public in 2010 under its new name, Museo Macro.

Odile Decq’s design brings a new dynamic to the old buildings. An entrance was created in the former stables (scuderie) on Via Reggio Emilia. The space between the old buildings has been covered and now provides room for large sculptures or installations. When we visited, we encountered the artwork ‘Yard’ by the American artist Allan Kaprow, made with car tyres. This piece was originally created in 1961 for the Gallery exhibition in New York and consists of hundreds of randomly placed used tyres. Visitors are encouraged to walk on the tyres and move them freely. This installation was presented in Rome for the first time in 2024, adapted specifically to this space.

The other entrance is located on the corner of Via Nizza and Via Cagliari. In an open corner between the original brewery buildings, a glass volume was added that rises above the existing structures. Under this mass, you enter a patio that leads you to the entrance. The patio is always accessible. The newly built structures and open spaces connect the buildings, floors, and surrounding streets. The large areas—such as the exhibition halls (with a surface area of 4,350 m²), the foyer, auditorium, and terrace (also called the panoramic garden)—are linked by staircases, elevators, galleries, and passageways. The bright red standalone exhibition room under a skylight, along with the similarly coloured bridges and ramps, make for a striking contrast against the sand-coloured and grey older buildings. Walking through these spaces, which we were fortunately able to do, offers various perspectives and viewpoints—both of the building and its surroundings. It is well worth visiting, even without an exhibition. How the experience changes with an exhibition in place, we couldn't judge.

The newest addition to Rome’s modern art museum scene is which stands for Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo (National Museum of 21st Century Arts). The museum is located on Via Guido Reni in the Flaminio district, just east of the sharp bend in the Tiber River. In 1998, the Ministry of Cultural Heritage launched an international design competition to create a museum on the site of a former military barracks. The Montello barracks, built around 1910, had always served a military purpose. The competition received 273 submissions from around the world. The winning design was by Zaha Hadid (1950–2016). She was a British architect of Iraqi origin. She studied mathematics in Beirut and moved to London, where she graduated in architecture in 1977. She worked at the Dutch architectural firm OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture) under Rem Koolhaas before founding her own firm in 1979. Zaha Hadid’s design convinced the jury thanks to its integration into the urban fabric and its innovative architecture. The design had urban planning, landscape, architectural, and curatorial qualities. Construction and realisation ultimately took more than ten years and cost around €150 million. In that same year, 2010, the design won the Stirling Prize from the Royal Institute of British Architects.

The building is not easy to explain. The sketch Jan made from above gives the best insight into how the new structure is interwoven with the existing barracks buildings. Several concrete forms twist from the building on Via Guido Reni, running parallel to the existing structures, and at the end wrap themselves around the adjacent building. The various ‘ribbons’ are largely separate from one another, and some are even detached from the ground. One of these ‘ribbons’ ends in a sort of visor that projects over the building and looks out over the city in a northeasterly direction.

From the ground floor, you get a completely different perspective of the building. We entered from the rear, via Via Masaccio. There, you see one of the elevated volumes with a fighter jet underneath it — upside down, in this case. On the site, concrete walkways are laid between large gravel stones. We arrive at a silver pavilion, the so-called MAXXI NXT Pavilion from 2024. It was designed by the architectural firm Grazzini Tonazzini. The pavilion is an abstract sculptural volume made of vertical panels of galvanised corrugated metal, forming a striking space with a pond in its centre. After a quick look inside, we continue along the concrete walkways. At several points, you’ll come across groups of silver-coloured columns that support the high, twisting structures. Following the concrete paths even further, we enter an intriguing space beneath them — filled with daylight — and search for the door in the glass wall.

The entrance hall is overwhelming. Above you, you see various ramps; the reception desk seems small and insignificant within it. High above the desk hangs an artwork by Maurizio Nannucci. This artwork was part of his major solo exhibition at MAXXI in 2015 titled ‘Where to Start From.’ Nannucci’s neon works are often large-scale and use bold colours, including red, to explore the relationship between art, language, and space. His work is designed to engage in a dialogue with the architectural environment, which fits perfectly in this MAXXI setting.

Finding your way through the museum becomes a small adventure. The most logical route is to head upstairs via stairs and ramps and gradually descend again. But we quickly discover the route is not always intuitive. Sometimes we find ourselves at the exit of a room rather than the entrance, or in front of a space that’s not accessible. Still, exploring this building is an adventure.

We saw some beautiful and inspiring artworks, but I must be honest: sometimes the art is overshadowed by the architecture. The building itself demands a lot of attention — especially in the upper levels. In the area we called ‘the visor,’ the art also has to compete with the view. This puts serious constraints on what can be exhibited and where. The exhibition on the ground floor — where Rome’s past is confronted with contemporary art — felt like scattered fragments in a theatrical set. It didn’t inspire or resonate with us.

MAXXI was established as a broad cultural campus and is managed by a foundation founded in July 2009 by the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities. According to what we’ve read, there is a packed schedule of programming: exhibitions, workshops, conferences, performances, screenings, and educational projects. One aspect worth mentioning is that people with hearing and visual impairments were actively involved in the museum's development. Everywhere there are braille signs and video guides in sign language.

Inside the museum, there’s a small café, Palombini al MAXXI. The museum’s restaurant is not located in the main building, but rather in an adjacent old barracks building that also houses the archive and several smaller exhibition rooms. You need to exit the main building and walk across the concrete paths to reach it. The upside is that from this building — or the terrace in front of it — you get an excellent view of the new building.

This is where our journey in search of modern and contemporary art in the ancient city of Rome comes to an end. It has offered us a diverse impression of how such art can be exhibited and the kinds of buildings used to do so in Rome. From the transformation of a small, historic villa element to a massive early 20th century park construction, to the transformation of a brewery and a military barracks — the museums are completely incomparable, which makes the experience all the more fascinating.

2025