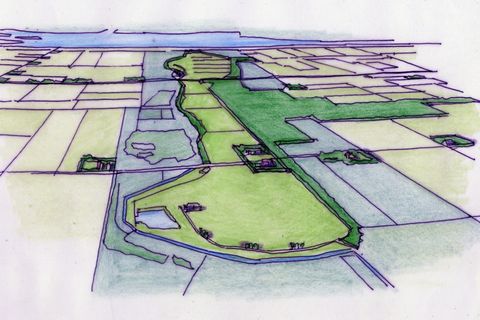

Where better to start than by going back to the 'genius loci'? What made this place special? This green environment where Louisiana stands has been shaped by humans for centuries. As a result of wars - between the mid-17th and early 18th centuries with the Swedes and the British - the landscape near the town of Humlebæck was fortified. After the threat diminished, the land was taken over by forester and former soldier Alexander Brun (1814-1893). He established the estate of Louisiana. Humlebæck was a small fishing village at the end of the stream between the elevated land and the Øresund (bæck=stream). Øresund is the strait between Denmark and Sweden, providing access to the Baltic Sea. In 1810, King Frederik VI ordered the construction of a harbour in Humlebæck. A German lieutenant colonel, who was also an engineer, designed a commercial harbour for fishing boats with a narrow channel leading to an inner basin on both sides of the stream. The basins could accommodate 100 gunboats. The king purchased the land from his grandfather, Constantin Brun, a prosperous merchant who had amassed wealth through trade and Denmark's neutral position during the wars. The basin eventually became Humlebæck Lake. The excavated earth was placed on the south side, creating a rampart. By the time the harbour was nearly complete in 1814, the war was over. What remained was a lake and a harbour. Ultimately, it was the grandson of the former owner, the aforementioned Alexander Brun, who would cultivate and restore the land. He named the estate after his wife, Louisiana. His first marriage was to Sophie Louise Alice Tutein (1989-1899), which lasted only twenty-five days. His second wife was Louise Penelope Webb (1830-1855), and they were married at the time he and his father attempted to repurchase the land from the king. That marriage ended when Louise died in childbirth, pregnant with their first daughter. In 1858, he married for the third time to Louise Wolff (1835-1926), and they had four children.