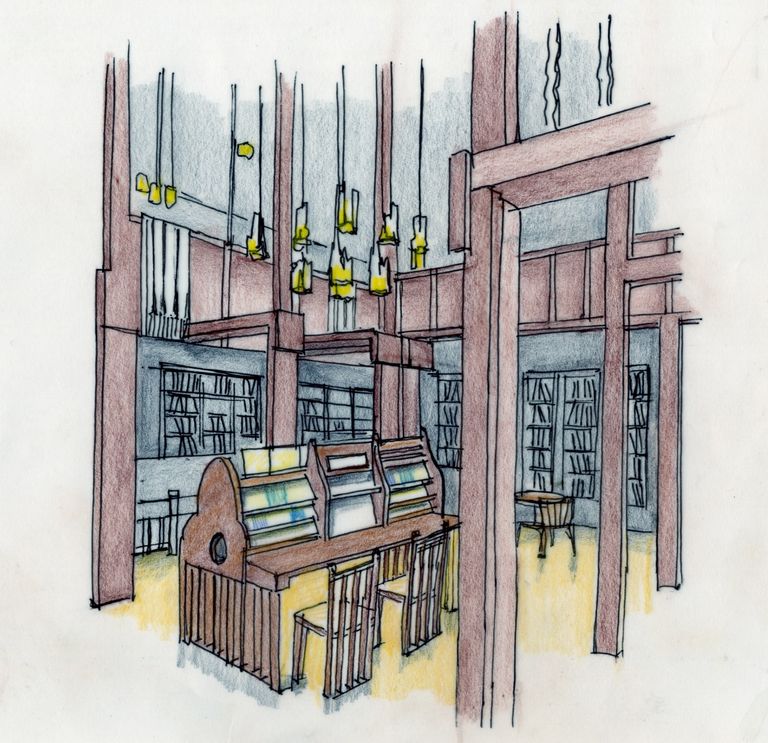

From the facades, you can infer the arrangement of the spaces inside: classrooms are located at the front behind the large windows, while other spaces - such as the theatre, library, offices, cloakrooms, and toilets - are situated at the back and sides. What makes this building so remarkable is not just the architecture, but above all the combination of exterior and interior. This was Mackintosh’s strength. The most extraordinary spaces were the library and the director’s room. Every description does injustice to the library, for the spatial effect of the interior with its daylight is difficult to put into words. It is a two-story space with a storage loft above, which also brings daylight into the library. The bookcases, the gallery on the upper level, and the furniture were all made of American tulipwood (yellow poplar). The wood was stained dark so that it looked like oak. Mackintosh had originally intended to use oak, but for budget reasons this was not possible. The woodwork is highly detailed, for instance, the balcony posts in the corners were worked with a gouge, and these planes were painted in four different colours. Mackintosh’s characteristic square and line patterns can be found everywhere. The director’s room is in the corner of the oldest part of the building and is fitted with a large window. Here, the walls are cream-white, and the decorations are organic, with plant motifs. All the walls are panelled, so that wall and furniture flow seamlessly into each other. The furniture is made of dark wood, as in the library. This later became the Mackintosh Room, in which several of his pieces of furniture and lamps were displayed. In every space the hand of the architect can be seen, whether in the corridors, the cloakrooms, or the staircases. Inside, too, you encounter metal ornaments; even the school bell is a work of art.