Rotes Wien (Red Vienna)

If one speaks about housing, one often refers to the model in Vienna. But what is that Viennese model? We will take a walk through history of housing in this city.

The news broke in November 2025: after careful consideration, the municipal council of Moerdijkin the Netherlands sees opportunities for expanding the industrial estate only if the village of Moerdijk eventually disappears. The national government and the province of North Brabant have postponed the final decision until the summer of 2026 in order to conduct further research into the consequences. How do you do that, make a village disappear?

The Netherlands is a country accustomed to growth. Decline is therefore a very difficult and far from self-evident phenomenon. We do not really know what it is like to say goodbye to the place where you felt at home, especially when it is not your own choice. In other parts of the world this happens more often. The major industrial cities in England now have only half the number of inhabitants they had in their heyday up untilthe Second World War. Large residential neighbourhoods were boarded up and later demolished. In Australia there are villages in gold-mining regions that are inhabited as long as the gold price is high enough, and that turn into ghost towns when the gold price falls too far. In the Netherlands, a limited number of villages disappeared in the 1970s due to dike reinforcement and the expansion of the industrial area near Delfzijl (Oterdum, Weiwerd, and Heveskes). There is, however, a very evocative example of vanished villages in our country on , but for that we need to go back to the middle of the 19th century.

Until recently, not many people knew much about Schokland, let alone where it was located, even though it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995. UNESCO’s statement of outstanding universal value for the site reads: “On Schokland, traces can be found of human habitation dating back to prehistoric times. It symbolizes the heroic, age-old struggle of the Netherlands against encroaching water. Schokland and its surroundings are an outstanding example of prehistoric and historic settlement in a typical water-rich natural landscape.”

In recent years there has been growing interest in the history of Schokland. This is mainly due to the book The Island of Anna by Eva Vriend and, published in the spring of 2024. I have gratefully made use of the information from this book. At the end of that same year there was an exhibition, The Soul of Schokland, at the Zuiderzee Museum in Enkhuizen. A year later a television series titled Longing for Schokland was released. There is a website about Schokland, a database of Schokkers, many books have been published about it, and as early as 1985 the Schokker Association was founded. This interest has everything to do with the fact that people want to know more about their origins, especially when it concerns a lost island. And we have a personal link here. Jan’s mother’s family comes from Schokland. His cousin Annette Diender is of Schokland descent on both her mother’s and father’s side; her surname is a genuine Schokland name. The woman on the poster of the exhibition in Enkhuizen is one of her ancestors, namely Jannetje de Graaf (1840–1916). She married Albert Klappe (1841–1933) in Kampen, who also came from Schokland. We will return to this family later.

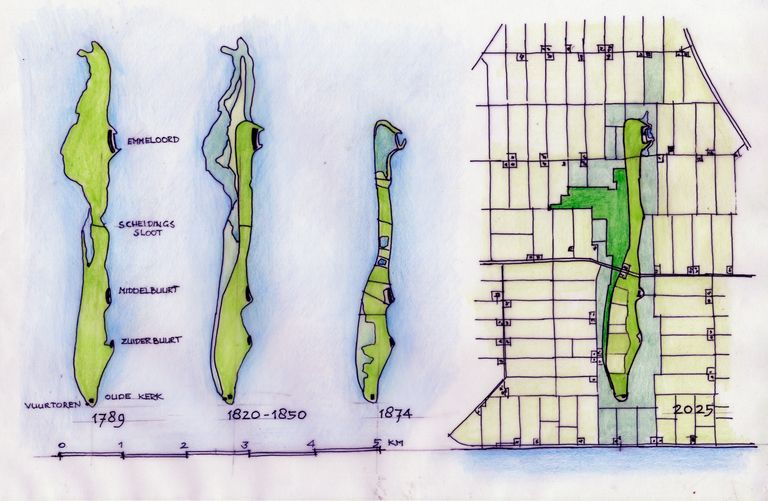

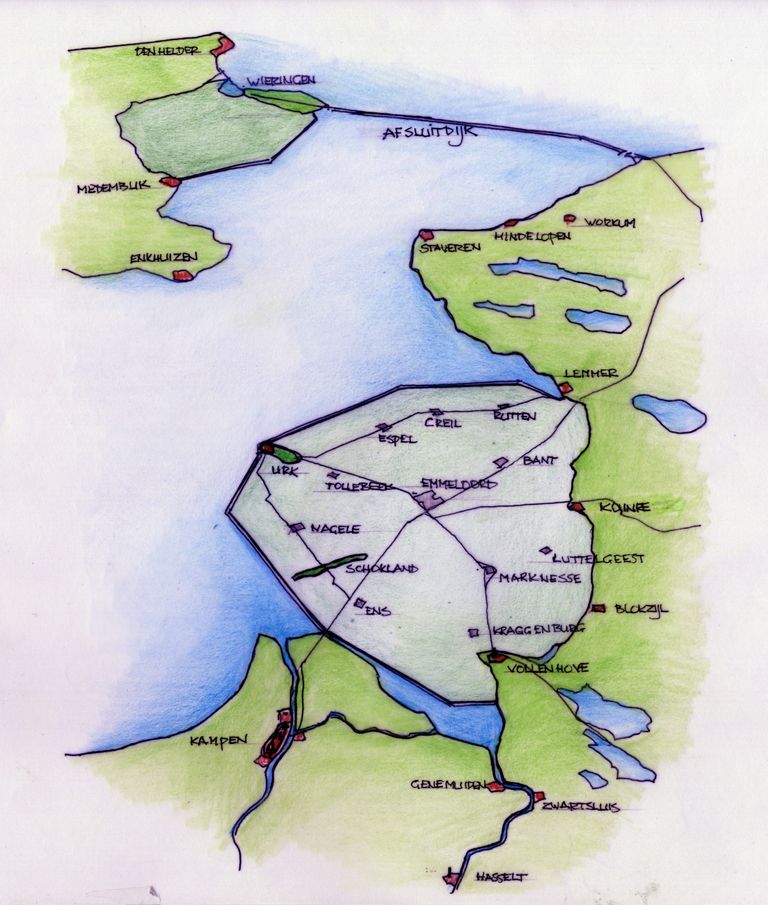

For a long time, Schokland was an island in the Zuiderzee, like , , and . It lay close to the mouth of the River IJssel near Kampen. The island therefore formed an important landmark for shipping, both for the merchant vessels of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and for the Zuiderzee fishermen. In the 17th century the island was much larger than what remained before the evacuation in 1859. Originally the island was inhabited by farmers, but the land became increasingly difficult to cultivate. The marshy ground flooded regularly, and storms on the Zuiderzee gradually eroded the western part of the island. What remained was the highest part of the island: a strip of land about 5km long and at most 300m wide. At high water or during storm surges, three terpen (dwelling mounds) remained just above water. Residential neighbourhoods were located on these: Emmeloord in the north, Ens in the middle, and Zuidert in the south. The land between the terpen was marshy and hardly passable. The neighbourhoods were connected by a narrow walkway behind a palisade. It was not easy to pass one another on this narrow walkway. But the islanders found a solution: the Schokker dance. When they met each other, they firmly grasped one another around the waist and then turned around each other.

The harbour of Schokland had been located in the north near Emmeloord since 1781. The village was therefore a fishing community. In the Middle Quarter (or Mill Quarter) at Ens, the public functions were located, such as the mayor, the constable, and the general practitioner. In the Southern Quarter (Zuidert) only a few families lived. At the southernmost tip of the island lay the cemetery, and there was a beacon light.

As early as the 17th century, fishing formed the most important source of income for the inhabitants of Schokland. At that time, Schokland had one of the largest fishing fleets on the Zuiderzee. Depending on the season, they fished both the North Sea and the Zuiderzee. Of all Zuiderzee fishermen, the Schokkers ventured most often onto the North Sea. During the summer months they fished for sole, haddock, and cod. In autumn they fished for Zuiderzee herring and eel. They had the best ships and took the greatest risks. Around 1800, the fishing industry on the island experienced its best years; Schokland had 80 vessels. Possibly as a result of overfishing, catches declined rapidly, with the consequence that skippers could no longer maintain their boats. In addition to fishing, the Schokkers were also active in cargo shipping: from Emmeloord’s harbour they sailed flat-bottomed vessels on regional Zuiderzee routes, from Amsterdam to Hamburg and via Zwolle to Cologne.

Schokland, though small, was a reflection of the Netherlands. It is hard to imagine, but the northern and southern parts of the island were administratively and ecclesiastically separate. Emmeloord belonged to the lordship of Kuinre, in the province Overijssel on the border with province Friesland. The lords of Kuinre were vassals of the Bishop of Utrecht and behaved as sovereign rulers. They had founded several medieval fortresses, the remains of which (after demolition between 1531 and 1535) came to light when the Noordoostpolder (which we will explain later) was drained. Their income came from toll collection, shipwreck salvage, fines, beer tax, and additionally from coin debasement. In 1476, the wealthy Catholic Utrecht family Zoudenbalch purchased the rights to Emmeloord. In 1614, their descendants sold Emmeloord and Urk to the Catholic nobleman Johan van de Werve from Antwerp. In turn, he sold Emmeloord and Urk to Amsterdam in 1660. For Amsterdam, this was a valuable addition to its trade routes, as Urk lay on the shipping route to the north and Emmeloord served as a sheltered stopover for inland skippers heading to the IJssel.

The administrative relationships guided the religious denominations on the island. Emmeloord was Catholic by tradition due to its owners; about two-thirds of the island’s inhabitants lived there. When, in 1573, the Sea Beggars of William of Orange defeated the Spanish fleet, the practice of the Roman Catholic faith was banned in the cities of Overijssel. Ens and the Zuiderbuurt therefore became Protestant. Ens, which also included the Zuiderbuurt, belonged to the province of Overijssel.

Throughout its existence, the island continually struggled against the water. In the Middle Ages, earthen dikes reinforced with compacted seaweed protected the island from the sea. Forerunners of Rijkswaterstaat proposed wooden sea defences, for which the piles were imported from Scandinavia. The piles were driven into the ground in double rows and filled in with rubble, reed leaves, or seagrass. However, shipworm, brought into the country by ships from Asia, also posed a threat, as it weakened the wood and thus the sea defences. Amsterdam grew weary of the island costing them so much money due to the constant need to repair the sea defences. In 1791, the States of Holland agreed to a transfer of the island to the national government. Responsibility for coastal defence then lay with the central authorities, and in 1804 Schokland received a stone dike. In 1806, the schout (bailiff) Eduard Seidel became the first joint mayor of Emmeloord, Ens, and the Zuiderbuurt. The struggle against the water continued. On the night of 4 to 5 February 1825, a storm and a spring tide coincided with large river discharges. Schokland was completely submerged. Thirteen people drowned, 86 houses became uninhabitable, and 26 houses were completely washed away. Emmeloord - lying lower than Ens - was the most severely affected.

In response to that storm, a major charity campaign was organised. King William I called for a national collection, and initiatives sprang up all over the country. The total proceeds eventually amounted to 2 million guilders, of which 100,000 guilders went to Schokland. Rijkswaterstaat restored the stone dike and made it lower and wider so that it would be less likely to break during storms. The reconstruction of the island could then begin. In 1830, Schokland had 675 inhabitants (147 families). In Ens, houses were repaired for civil servants (including the Rijkswaterstaat (Directorate-General for Public Works and Water Management supervisor)), the constable, the schoolteacher, and the doctor. From 1831 onward, it was also the seat of Mayor Gerrit Jan Gillot, while the municipal administration remained in Emmeloord. Gillot was the son of a Reformed minister from Ens.

In 1838, the renovated harbour was completed. The newly built church in Ens opened its doors in 1834, and the stone St. Michael’s Church in Emmeloord in 1842. Income from fishing declined, and poverty on the island increased. In 1839, two weaving workshops were opened to promote employment, one in the former town hall in Emmeloord and one in Ens. They were called poor schools. However, these too were short-lived. Due to competition from mechanised textile factories, the weaving workshops were forced to close in 1857. Since 1841, there had been a ‘Committee for Regular Relief’ to distribute assistance to the needy, which many Schokkers relied upon. In 1854, the director of the Department of Domains in Zwolle concluded that Schokland was probably the poorest municipality in the Netherlands. The Zuiderbuurt had by then dwindled to about a dozen houses. Protecting the inhabitants no longer outweighed the costs, Rijkswaterstaat reasoned, and it advised that the hamlet be evacuated. The residents received compensation on the condition that they dismantle their houses and take them with them. They moved to Ens and repaired dilapidated houses using materials from their old homes.

In 1857, Pastor Herman ter Schouw could no longer bear the situation after four parishioners had died of hunger. He turned to the newspapers, but also to the Minister of the Interior, the King’s Commissioner in Overijssel, and the House of Representatives. Something had to be done. In the first months of that year, Jacob Ortt, an engineer with the Water Management Department in Kampen, had written a report on Schokland in which he proposed an evacuation. It was in the interest of the islanders, but also of the state, which in the long term would have to spend less money on strengthening the dikes and on the salaries of civil servants. The proposal was submitted to the Provincial Executive (Gedeputeerde Staten) on 2 April 1857. A distinction was made between the wealthy - who were to be encouraged to leave - and the poor, for whom it would in any case be better to depart. The residents received provisional contracts in which they agreed to the evacuation compensation and pledged to dismantle their houses. The latter was included to ensure that the Schokkers would not return. Compensation for the Schokkers was set at 2¼ times the assessed value. In February 1858, the Minister of the Interior wrote to the King’s Commissioner that the Schokkers had to leave the island. Two officials were sent to the island to prepare the operation. In the autumn, a special parliamentary committee was established to consider the issue of the evacuation, for the first time in Dutch history.

With the evacuation came another problem: where were the Schokkers to go? They did not have a good reputation, partly as a result of nationwide campaigns portraying the Schokkers as needy, but also because of their unusual living conditions on the island. Many Schokkers relied on poor relief; none of the mainland municipalities wanted to take them in. A majority in Parliament believed that the Schokkers should not be sent to one single place, for fear that they would ‘retain their vices and become a burden to the other inhabitants. Inevitably, special police supervision would then have to be imposed on them’ (from The Island of Anna). It was believed that by dispersing the inhabitants, it would be possible, with the help of social and religious education and the example of other residents, to guide the Schokkers onto the right path. To prevent the new locations from being burdened with poor relief, municipalities could claim those costs from the state. On 18 November 1858, the House of Representatives approved the ‘Bill containing measures for the evacuation of the island of Schokland.’ A month later, the Senate also approved it, and the evacuation became a formal decision.

The municipalities along the Zuiderzee seemed the most logical places of settlement for the Schokkers. Mayor Gillot and the King’s Commissioner of Overijssel wrote to these municipalities. Monnickendam, Edam, Hoorn, Texel, and Enkhuizen quickly responded with negative replies. Medemblik was wary of ‘this kind of people.’ An anonymous letter in a newspaper elaborated on this: “You see, there is such a great difference between the North Holland race of people and that of the Schokkers.” What does this make you think of—in the present day? Resistance was also strong in Kampen. There was fear that the Schokkers’ small houses would disfigure the city promenades. In addition, the difference between the predominantly Catholic and poor Schokkers and the wealthy Reformed Hanseatic town was considered too great.

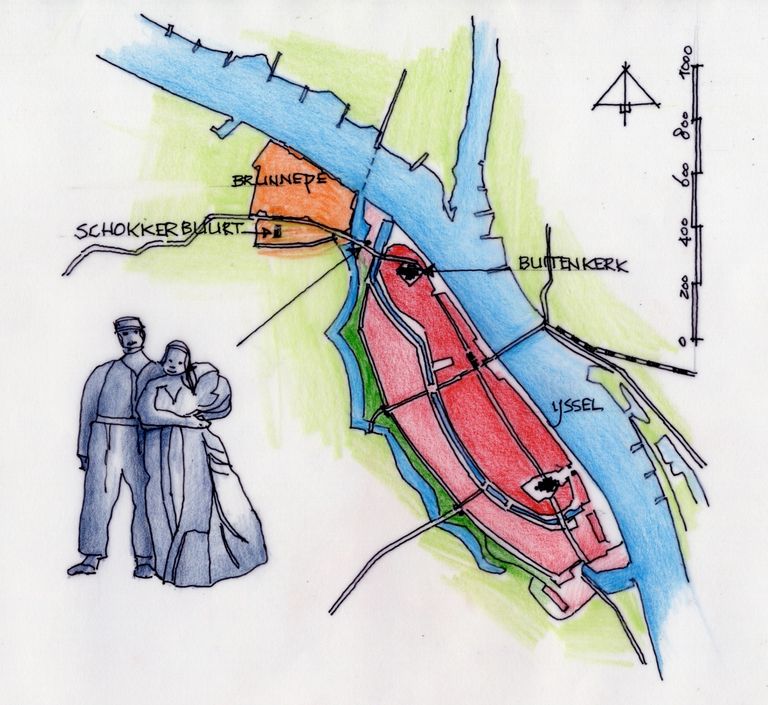

Nevertheless, became the largest place of settlement: more than 470 people moved to this city. A total of 129 Schokkers ended up in , an eastern Zuiderzee town that had been the administrative centre of the northern Netherlands in the 17th century. About 35 settled in –Edam, and approximately 25 Protestant Schokkers went to live on Urk. What few people know is that a small group ended up in Nijverdal because of employment opportunities in the textile industry.

The working-class neighbourhood of Brunnepe in Kampen owes its name to the brown water of the peat stream that flowed into the IJssel north of Kampen: brun apa in Germanic. It was an independent community outside the city walls, with its own harbour and market. The municipality considered Brunnepe’s somewhat isolated location an advantage for the settlement of the Schokkers. The people of Brunnepe attended services at the Catholic Buitenkerk (Outside Church). This church dates from the 14th century and was originally located outside the city walls, hence the name. This is where Jan’s family enters the picture. Jan’s mother was born in Kampen; she was the eldest daughter of the sexton of the Buitenkerk. Jan’s grandfather, Martinus van Mierlo (1902–1973), was a cigar maker, worked at an insurance company ‘De Nederlanden van 1870’ and was sexton of the church from 1928 to 1968. He was married to Grada Grootjen (1903-1954). The parents of Jan’s grandfather came from both sides of Schokland; his father’s parents were Johanna Grootjen and Jacob Klappe. Jan’s mother regularly worked in the shop by the church, where statues of saints and rosaries were sold. There she met Jan’s father in 1956. He came to Kampen more often because his sister had married a man from Kampen. Through the church, the Van Mierlo family became well acquainted with the descendants of the Schokkers. Jan’s mother’s younger sister, Aunt Lidy, met her husband Ab Diender. His parents were Schokker descendants: Jannetje Klappe and Johannes Diender. His grandmother was Jans de Volendammer, probably the daughter of Jannetje de Graaf (from the exhibition poster).

Until the flood disaster of 1825, there were eighty small houses in Brunnepe, but the area outside the city wall was also partly flooded. It was mainly a farming village. Arnoldus Legebeke, a Catholic schoolteacher from Emmeloord on Schokland, had married a wealthy widow from Kampen. She owned several plots and buildings in the city. One of these properties was located in the middle of Brunnepe and had a large backyard. He demolished the building and divided the land into 21 plots, which he sold to the Schokkers. In total, 97 Schokkers came to live there. The Schokkers’ houses were built along two streets: Schokkersbuurt and Emmeloordstraat. Later, more street names in the neighbourhood referred to Schokland. The houses were rebuilt using the materials the Schokkers had brought from the island, but they were not reconstructed in the same way. The typical wooden gabled façade was missing; instead, they were built as semi-detached or terraced houses. The walls were not wooden, but brick built. The wood they had brought from the island was used inside the houses.

With the arrival of the fishermen from Schokland, Kampen’s economy grew. In 1867, a new harbour (the Buitenhaven, Outer harbour) was constructed, bringing new employment. Fish traders, fish smokers, net makers, and ship repairers settled there. Around 1900, there were still one hundred fishing vessels. In 1955, most of the Schokker houses were demolished. The Buitenhaven eventually became the site of the Schokker Monument, but not without struggle. In 1989, a special working group consisting of representatives of the Schokker Association, the Brunnepe neighbourhood association, and the Municipality of Kampen took the initiative to create a monument in memory of the former island of Schokland and its inhabitants. In 1991, the statue was unveiled in the presence of 375 Schokker descendants. It is a life-sized bronze sculpture of a Schokker couple, Harm and Aal Diender, with a child. Their posture and facial expressions reveal the sorrow caused by the forced departure from their beloved island. The young fisherwoman is pregnant, a reference to the fact that despite all the misery of the evacuation, there was still hope for a new life and a new future. The sculpture was made by the Irish visual artist Norman Burkett, who lives in Enschede. Due to dike reinforcement works, the municipality removed the statue and placed it in storage. Two years later, it was placed on the IJssel quay. Partly as a result of the Schokker protest, under the name ‘Misplaced’, the municipality eventually relented, and in 2018 the statue was given a place near the Buitenhaven. However, not everyone agrees with the direction in which the statue faces (not toward the water or Brunnepe). The original idea was that the couple should stand with their backs to the city of Kampen.

You can imagine that the Schokkers felt at home in Brunnepe fairly quickly. They belonged to the same socio-economic class, shared the Catholic faith, and lived quite separately from the wealthier Reformed population of the city. In addition, the fishermen were able to continue practicing their trade. In Vollenhove, the Schokkers found themselves in a predominantly Dutch Reformed community. Just before their arrival, the Bishop of Utrecht had established a parish there, and you can imagine that the parish priest was pleased with the arrival of the Schokkers. But it was not only the priest who welcomed the newcomers; the municipal authorities did as well. In the first half of the 19th century, the city had seen employment decline, and now the arrival of fishermen also attracted related industries. Unlike in Brunnepe, the Schokkers in Vollenhove were spread throughout the city. Vollenhove ultimately proved to be more of a transit station for the Schokkers, many of whom later moved elsewhere.

In Volendam, the Schokkers came to live among Catholic fishermen and integrated into the community fairly easily. The book Het eiland van Anna mentions that between 1880 and 1920, 42 marriages took place involving Schokker descendants, and that none of them married a descendant of Schokland. On Urk, a number of houses were built for the Schokkers south of the then harbour and in the compact old town centre. Today, this area is called the Schokkersbuurt (Schokker neighbourhood), and there is a Schokkerstreet. Ultimately, the Schokkers integrated easily into this fishing village; it was mainly the Protestant Schokkers who went to Urk.

How did the Schokkers fare after the evacuation and relocation? It is clear that the Schokkers faced serious financial hardship. The evacuation compensation was spent on building houses, and in winter the fishing industry generated less income. Applications could be made to the municipalities for the Schokker allowance from the state (so that the costs would not fall on the municipal poor relief fund). It is important to note that women born on Schokland who were married to a non-Schokker were not entitled to this allowance; widows were. In 1876, 61 Schokkers applied for the Schokker allowance, and thirty years later this number had risen to 65. The municipality of Kampen continued to claim these costs from the state until 1940, as long as Schokkers born on the island were still alive.

Major changes were still to come for the Zuiderzee. In 1886, the Zuiderzee Society was founded by a number of notable figures. This association was tasked with investigating whether reclamation of the Zuiderzee would be feasible. Engineer Cornelis Lely was a prominent member and later chairman of this association. In 1891, he designed his first plan for the closure and reclamation of the Zuiderzee. In 1913, by which time Lely had become Minister of Water Management, land reclamation was included in the government program, despite protests from the fishing industry. The flood disaster of 1916 proved decisive, and in 1918 Parliament approved the plans. Construction of the Afsluitdijk began in 1927: a 32.5km dam from Den Oever in North Holland to Friesland. In 1932, the Afsluitdijk was completed and the Zuiderzee was renamed the IJsselmeer. This was a heavy blow to fishing along the former Zuiderzee, and a second blow for the Schokkers. A Zuiderzee Act was introduced, which included Zuiderzee support: “by law, measures are regulated and established to provide compensation to the Zuiderzee fishing population for the damage that the closure may cause.” A meagre consolation.

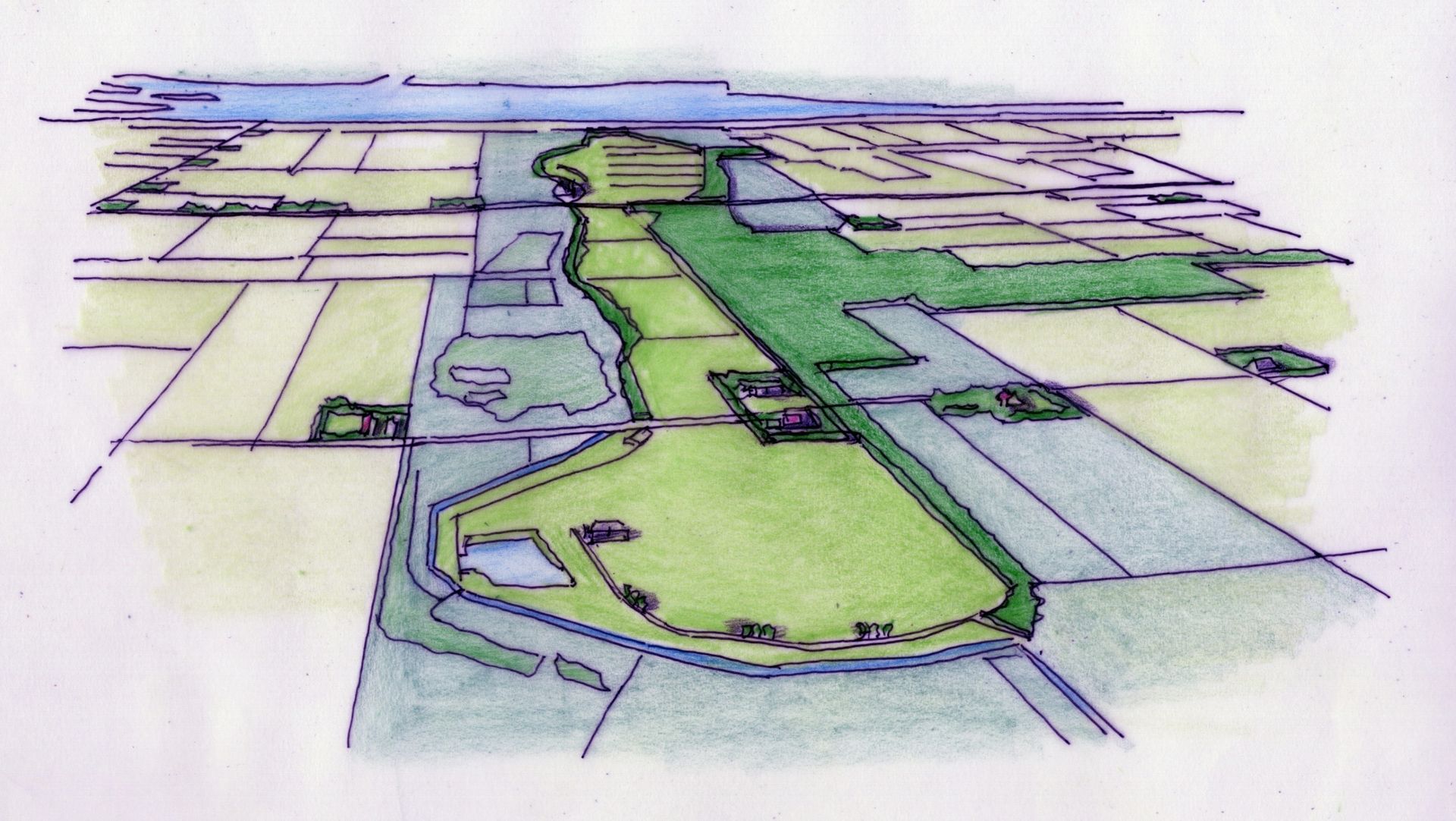

With the adoption of the Zuiderzee Act in 1918, the construction and reclamation of the IJsselmeer polders—the “Lely Plan”—was also decided upon. Preparatory work began in 1936, and in 1937 the construction of 31.5km of dike was put out to tender. On 3 October 1939, the dike between Lemmer and Urk was closed, and Urk was no longer an island. On 13 December 1940, the dike on the southern side of the polder near Schokkerharbour was closed; the total length of the dikes now amounted to 54km. At the beginning of 1941, the pumping out of the polder began. The polder officially fell dry on 9 September 1942. From that moment on, Schokland was no longer an island either; it now lay in the middle of the new polder. Even during the Second World War, work on the reclamation continued, as the acquisition of additional agricultural land (with food production) was an important objective for the occupiers as well. This does not alter the fact that the polder also became known as the National Hideout Paradise as approximately 20,000 people in hiding found refuge there.

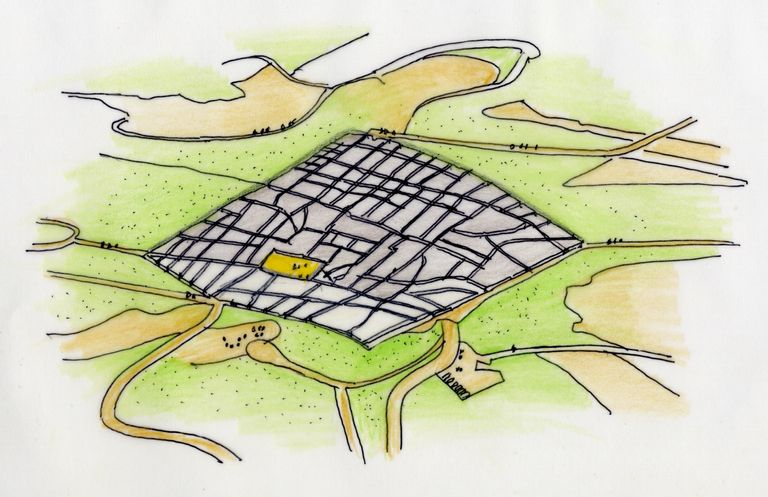

Various names were considered for the new polder. In 1944, the name Urkerland was officially recorded, as were the names of the villages. During the war years, the names Schokkerwaard, Urkerwaard, and New Schokland were also used as alternative names for the polder. In 1948, Noordoostpolder (North East Polder) became the official name, abbreviated as NOP. From the establishment of the municipality of Noordoostpolder in 1962 until the creation of the province of Flevoland in 1986, the polder belonged to the province of Overijssel; before that, the area was administered directly by the national government. Schokland provided the names for the new towns of Emmeloord and Ens. On maps and aerial photographs, Schokland is easy to recognise because it does not conform to the strict grid of roads, waterways, and polders of the Noordoostpolder. Even today, the former island still lies higher than its surroundings, and one can imagine the waving grain as the sea. On 1 November 2008, the Noordoostpolder gained a village (the newest village in the Netherlands): Schokland. The new village of Schokland consists of no more than four households, a museum, a restaurant, and the residence of the lighthouse keeper.

One may wonder whether the Schokker heritage is sufficiently honoured by preserving this small piece of land and small number of buildings. As the story of the house that Anna bequeathed to the Zuiderzee Museum (from the book by Eva Vriend) shows, we have not always been particularly careful with other tangible reminders of the island either. Even more complex is the history of the remains of the old Schokker cemetery. During the Second World War, Professor De Froe, professor of anthropobiology and human heredity at the University of Amsterdam, excavated the bones together with students. De Froe hoped that skull and bone measurements would reveal more about the physical characteristics of the Schokkers. It later became clear that this was done in the context of racial research, which came to be viewed in a very different light during and after the Second World War. The bones of 147 skeletons remained at the Anatomical Laboratory. The Schokker Association worked toward reburial. When sufficient funds had been raised for the restoration of the island - including the church ruins on the southern tip of the island - the time was ripe for reburial in 2003 at that church. A service was held in the former church in Ens, led jointly by a minister and a priest.

In 2007, a monument to the former inhabitants of Schokland was unveiled near old Emmeloord. It stands on the existing cemetery next to the site of the former St. Michael’s Church from 1842. This church was dismantled during the evacuation and rebuilt in Ommen, because the diocese wanted to establish a new bishopric there. The church was demolished again in May 1940. The artwork by Marianne Meinema and Annet Bult consists of a horizontal steel frame mounted on slender vertical posts set in a shell path. Four benches are placed opposite one another in a crosswise arrangement. Cut out of the frame are the names of the Schokkers buried here. One finds the most common surnames in Emmeloord, including Diender, Grootjen, Klappe, and Kwakman. The names can be read as shadows cast on the ground. The site has also been designated as a scattering field for the ashes of deceased Schokker descendants, and it is still regularly used.

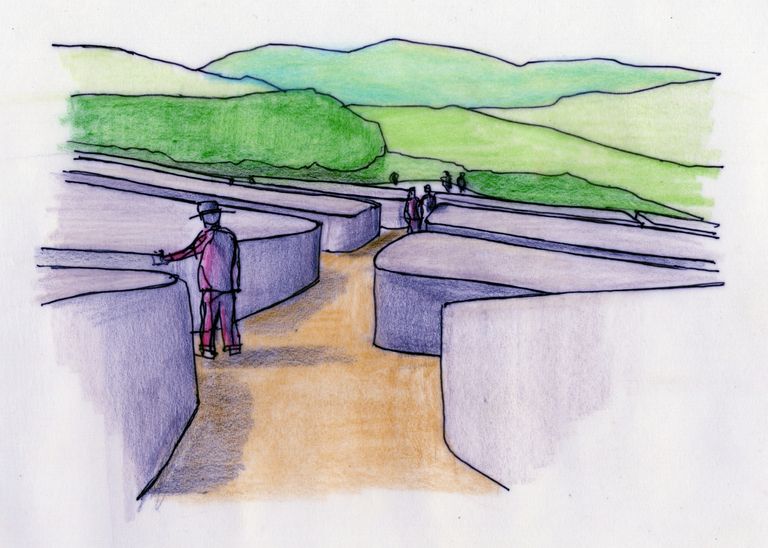

There are, of course, different ways to give form to saying farewell to the place where you felt at home. A striking example is Gibellina in Sicily. In January 1968 an earthquake struck there, claiming 251 lives and leaving many people homeless. The damage was so extensive that rebuilding the small town was never considered. The mayor chose instead to build a new town several kilometres away: Gibellina Nuova. He enlisted the help of artists and architects. A new museum of modern art was built, and many artists donated artworks free of charge. A new city church was also built, the Chiesa Madre (1985–2010), as well as a theatre and conference centre (1976). Unfortunately, the new town has since fallen into decline, but there are still some sixty artworks to be found in the public space. The most impressive artwork can be found on the site of the old town, Gibellina Vecchia. There one finds the Grande Cretto, or Cretto di Burri, named after the artist Alberto Burri (1915–1995). He literally cast the memory of the town in concrete. The old street pattern has been preserved in a crust of rubble and concrete; one can walk through the cracks (cretto). The artwork covers an area of 80,000 m².

Whether the Grande Cretto offers consolation to the former inhabitants or contributes in any way to the memory of feeling at home - or belonging - is unclear. What is clear, however, is that great effort was made by many people to draw attention to this history and to give it a place. It is also clear from the experiences of Schokkers, that such a farewell should not be taken lightly. It requires great care and it is not solely the responsibility of the people from the evacuated place. Financial, physical, and emotional support from others outside the affected community is necessary, and creativity can help make the process more bearable. Our thoughts turn to Moerdijk, and the hope that taking the time to consider the best actions will help those affected by this shock announcement.

2026